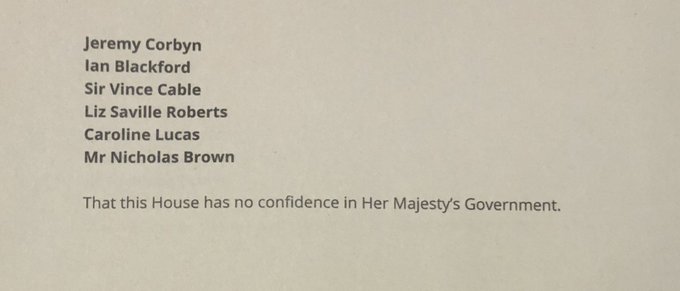

A day after British MPs voted down her preferred deal for Brexit, Prime Minister Theresa May faces a no-confidence vote put forward by opposition Labour Party leader Jeremy Corbyn.

The Conservative leader is likely to survive the vote, as rebels within her own party who rejected her signature policy say they will support her to prevent what would almost certainly lead to a new general election.

May’s last election gamble in 2017, which she hoped would give her a strong mandate to deliver on Brexit, cost the Conservatives their majority.

Tuesday’s 202 to 432 vote government defeat was the worst in modern history.

With opinion polls putting the two leading parties neck and neck a new vote would likely either force the Conservatives out of power, or result in a continued stalemate.

But Labour’s statements in the aftermath of the vote capture a sentiment widespread even among May’s traditional backers; that the prime minister does not have a clear way out of the crisis.

Corbyn tweeted: “Theresa May has reached the end of the line.”

While Scottish Labour leader Richard Leonard said the party would settle for nothing less than another election.

“The Tories have failed miserably on Brexit and it is no surprise Theresa May’s deal has been rejected by such a massive margin,” he said, adding: “We need a general election and a Labour government to break the deadlock and end austerity.”

While they are no fans of the Labour leader, the United Kingdom’s right-leaning newspapers did not attempt to dress up May’s woes.

The Daily Mail, which backed her deal, ran the headline “Fighting for her life” on its front page, while the right-leaning Daily Telegraph declared “The crisis is finally upon us.”

The opposition, however, has been short on details when it comes to what happens next. The spectre of Brexit grows larger each day. The deadline for the UK signing off on a deal with the European Union is March 29.

An election would take weeks to organise and hold, and any new parliament would have to agree on a deal that the EU also accepts.

Whether a new election is announced or not, and barring a shock resignation that would further compound the crisis, the burden of concluding Brexit remains May’s for now.

The most immediate short-term remedy for the prime minister would be to extend Article 50, the EU’s constitutional mechanism for leaving the bloc.

The article states that the process of leaving must be completed within two years of the EU being formally notified of a country’s intention to leave.

In December, however, the European Court of Justice said the process could be unilaterally cancelled without seeking the approval of all EU states. Member states are also open to extending the process.

May has said she does not “believe” in extending Article 50 but has not ruled out doing so.

Such a move would bring temporary relief but is likely to enrage the hard right and Brexit supporters, who see it as a delaying tactic.

‘No-deal’ Brexit

Politically, the prime minister must tread carefully.

When it comes to Brexit, no faction within parliament is big enough to get its deal through, and with a country deeply polarised on the issue, any move seen as too soft or too hard on the issue risks losing potential voters.

So what options does the prime minister have beyond a temporary extension of Article 50?

A “no-deal” Brexit would see the UK leave the EU without and agreement to keep in place any shared trade, economic, security, and other political structures.

The UK would then revert to trading with the EU and the rest of the world on World Trade Organisation terms.

Seen as a doomsday scenario by most Britons, it has support among the hard right.

The UK would have to agree to hundreds of new trade deals to replace those lost by losing its EU membership, which would likely lead to a rise in prices and a slowdown in economic growth.

May has repeatedly warned against such a departure from the EU but – publicly at least – accepts it is a possibility.

Renegotiate existing deal

May will likely head back to Brussels to plead with EU leaders to offer her more favourable terms.

The EU, however, has refused to offer concessions and French President Emmanuel Macron said he considers May’s failure to reach an agreement an “internal UK politics problem”.

EU Brexit negotiator Michel Barnier said it is up to Britain to come forward with ideas in wake of the defeat. He said the EU is now “fearing more than ever” a chaotic departure of the UK from the bloc.

EU Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker also said a disorderly Brexit was more likely while Donald Tusk, the chairman of EU leaders, suggested Britain should now consider reversing Brexit altogether.

Even if the EU agrees to concessions, May would have to put them to parliament. Given the unprecedented scale of the first defeat, it is unlikely a modified deal would pass without major changes.

Call for a second referendum

Demands for a second referendum have grown over the past year with those behind the “People’s Vote” campaign calling for an option to remain in the EU.

There is no guarantee that would work either.

Polls show while a majority of Britons would prefer to stay in the EU, the margins are small and have shifted little since the original 2016 referendum.

May has dismissed the idea as a “betrayal” of those who voted to leave in 2016, and any attempt to reverse course would also enrage the hard right.

A successful boycott movement could also delegitimise the results of a new referendum, throwing the UK into further political crisis.

Blame it on Brexit: The cost to the financial services industry

SOURCE: AL JAZEERA NEWS